What happens to EV batteries after they can't be used in cars?

One of the biggest concerns for car owners as the world switches to electric vehicles (EVs) is what happens to batteries as they're used.

Various studies have been conducted: for instance, during a taxi trial at Gatwick Airport, five Tesla Model S 90D cars completed 1.5 million miles, each driving around 300,000 over a three-year period. Afterwards, the batteries were at an impressive 82% state of health (SoH).

The Model S was initially offered with an unlimited-mileage, eight-year warranty. However, that was reduced to 150,000 miles, eight years and 70% SoH in 2017.

Tesla will replace the battery in your recent Model S or Model X if it drops below 252-mile range in less than 150,000 miles or eight years.

Mercedes-Benz, on the other hand, offers a 100,000-mile, eight-year warranty on its EV batteries, and it's the same for the Jaguar I-Pace. It's clear, then, that second-hand electric car owners will have queries around long-life battery ownership.

That EV batteries degrade faster in the first year or two is widely known. The first year dropped about 8% in 100,000 miles in the Gatwick trial, but after that, the degradation was almost a straight line of 5% per year (driving 100,000 miles per year). At this rate, the vehicles would have easily passed 500,000 miles before they reached 70% SoH. This is more than three times the warranted distance.

Guest editorial originally published in Autocar sister title Car Aftermarket Trader (CAT) by Alex Johns, sales development manager at Altelium

How do I stop my EV's battery degrading?

First, a technical term: knee-point. This is when a battery undergoes a rapid degradation – something that every battery and vehicle manufacturer is obviously trying to avoid. The phenomenon is subject to a great deal of study, but what is clear is that, on the assumption that your battery is well manufactured (without faults), then knee points tend to occur if the battery is overstressed.

This occurs through too much supercharging (which raises the battery temperature too much too often) and charging and discharging to the maximum too often. Running a battery from 10% or more to less than 90% state of charge (SoC) most of the time and rarely supercharging it will help ensure it lasts longer. 'Resting' the battery once a week for a few hours at a fairly low SoC will also help.

Battery SoH is an absolute measure and will become the currency of battery trading in the future. Although EV drivers focus on SoC, because it tells them if they have enough power to reach their destination, the measure that really matters in economic terms is SoH.

What could happen to EV batteries after their SoH drops below 70%?

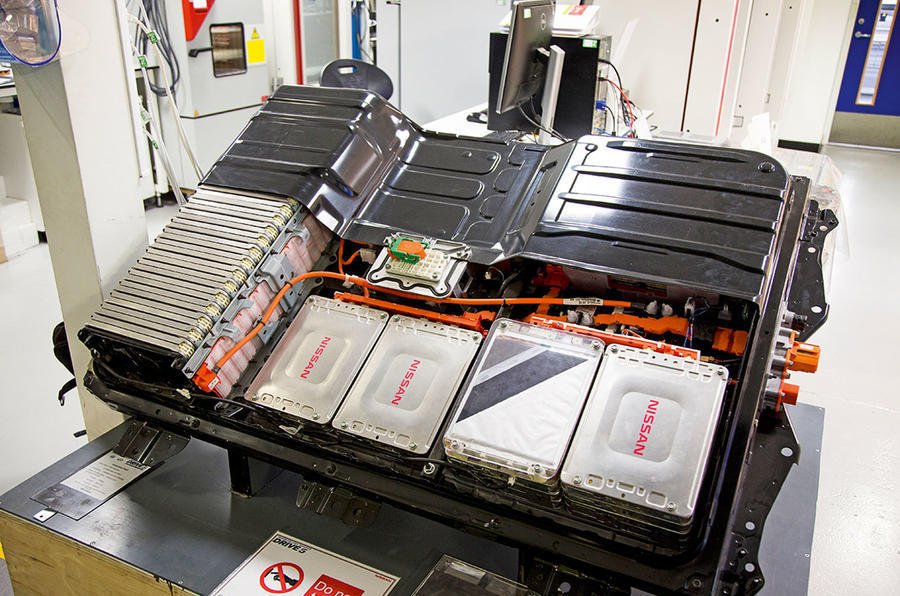

A battery at 70% SoH may no longer be suitable for use in an EV, but it will be very useful in a 'second life' battery energy storage system (BESS) for several years (at least five) until it reaches 50% SoH, at which point it's no longer commercially useful. The industrial knee-point has been reached.

The BESS market is about to take off dramatically, just like other technologies have, such as computing power, network capacity and data storage.

For example, the Hornsdale Power Reserve in Australia, completed at 150MW/194MWh, held the title of the world's largest BESS for just three years. It was surpassed last year by the Gateway Energy Storage in California, which has a huge storage capacity of 230MWh, last year.

But this is less than half the capacity of the new Tesla plant planned at Moss Landing in California, at 730MWh. All of them, however, will be dwarfed by the 1500MW/6000MWh installation that was given approval in October, also in Moss Landing, for Vistra Energy.

It's the BESS market that is revolutionising the energy market, allowing energy from renewable sources of wind, sun and water to be stored.

This dramatic increase in the size and number of large BESSs mirrors growth in the small BESS market for domestic use, such as the Tesla Powerwall and the UK's Powervault.

Most BESSs are made using first-life batteries, but an increasing amount are being made from second-life batteries from EVs. Tesla has reported how its batteries will last for a million miles or even longer (presumably to 70% SoH) but has made no mention yet of using second-life batteries in BESS or any other second-life use.

The cost of second-life batteries is so much lower than first-life batteries that the return on investment is both higher and economically attractive in its own right, despite the shorter lifespan of the second-life BESSs.

A battery at 75% SoH will last half the length of the time of a new battery but cost far less than half the amount to buy. This is exactly the sweet spot where the 'missing' Tesla batteries will be: not yet ready for complete recycling but also no longer in cars on the road.

Related News